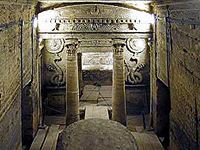

Catacombs of Kom el Shoqafa

|

| Catacombs

in Alexandria |

The catacomb of Kom El-Shuqafa (Shoqafa, Shaqafa)

is one of Alexandria's most memorable monuments. Identified

as "a tour-de-force of rock-cut architecture which would be

remarkable in any period," the Great Catacomb defies comprehensible

description. Its vast, intricately decorated interior spaces

cut at so great a depth into the rock present an enormity

of experience outside the normal human realm and tell us of

a level of technological expertise equaling enterprises of

modern subways and tunnels while far surpassing them in aesthetic

response.

Kom El-Shuqafa is the Arab translation of the ancient

Greek name, Lofus Kiramaikos, meaning "Mound of Shards" or

"Potsherds." Its actual ancient Egyptian name was Ra-Qedil.

These catacombs date back to the late first century

AD. Kom El-Shuqafa lies on the site where the village and

fishing port of Rhakotis, the oldest part of Alexandria that

predates Alexander the Great, was located. They are situated

in the Karmouz district of western Alexandria, which is now

one of the most densely populated districts of Alexandria.

This district itself was used by Mohammad Ali Pasha to defend

the city. Then the area was destroyed in about 1850.

On its western side, as usual in Egyptian funerary

practices, lies its “City of the Dead.” However, while the

ancient Egyptians mummifed their dead, the Hellenistic custom

was for cremation. This area used to contain a mound of shards

of terra cotta which mostly consisted of jars and objects

made of clay. These objects were mostly left by those visiting

the tombs, who would bring food and wine for their consumption

during the visit. However, they did not wish to carry these

containers home from this place of death.

Excavations of the site began in 1892 but no catacombs

were actually found until Friday, September 28th, 1900 when

according to tradition, by mere chance, a donkey pulling a

cart fell through a hole in the ground and into one of the

catacombs. However, in reality, the discovery was made on

that date by an Alexandrian, Monsieur Es-Sayed Aly Gibarah,

who immediately sought out Botti at the Museum, explaining

that, "While quarrying for stone, I broke open the vault of

a subterranean tomb; come see it, take the antiquities if

there are any, and authorize me to get on with my work without

delay."

Little did Botti know what glorious finds he would

make, but this day he would not visit the catacombs. He later

explained that, since the discovery happened on a Friday,

a day off for most Muslims, the museum was very busy and he

had meetings that day. Besides, he had often been called out

to see valueless work, and was therefore very satisfied to

leave his visit until the next day. However, because the stone

worker was so insistent on getting back to work, he allowed

his inspector, Silvio Beghe, and an attendant, Abdou Daoud,

to leave the museum at five o'clock, one half hour early,

in order to visit the find and report back to him that evening.

The next day, he would be astounded by this discovery. The

site was opened for the public only in 1995 after pumping

the subsoil water from the 2nd level.

The Necropolis is of the catacomb type that was widespread

during the first three centuries in Italy (Rome). This type

of catacomb was usually limited to the burial of deceased

Christians. It was, to the believers of this new religion,

an asylum where they could be safe from the injustice of the

emperors. In the tombs below the cathedral of Saint Sebastian

in Rome we can find catacombs in the form of streets stretching

for many miles, with tombs to their sites. However, in the

Necropolis of Kom el-Shuqafa there is no trace of Christian

burials.

The catacombs are unique both for their plan and

for its decoration which represents a melding and mixing of

the cultures and traditions of the Egyptians, Greeks and Romans.

It was a place where people seemed to have a talent for combining

rather than destroying cultures. Though the funerary motifs

are pure ancient Egyptian, the architects and artists were

clearly trained in the Greco-Roman style. Here then, we find

decorations related to ancient Egyptian themes, but with an

amazing twist that makes them quite unlike anything else in

the world.

Scholars believe that the catacombs at first may

have served only one wealthy family that still practiced the

ancient Egyptian pagan religion. However, they were expanded

into a mass burial site, probably administered by a corporation

with dues-paying members, perhaps because of its pagan heritage.

This theory could explain why so many chambers were hewn from

the rock. In its final stage, the complex contained over one

hundred loculi and numerous rock-cut sarcophagus tombs.

Some believe that the scale of this endeavor precludes

the catacombs as representing a private monument. Alan Rowe

thought that the complex was cut originally as a Serapeum

rather than as a tomb complex. Though there is no solid evidence

to support his theory, the complexity of the undertaking seems

to almost preclude private patronage.

These tombs represent the last existing major construction

related to the ancient Egyptian religion. This was also the

case in the Pankrati tomb in Rome. They dug out loculi and

then closed the openings with marble and limestone. The name

was written on the tomb in a different way from Italy, depending

on the artistic style used. At Kom El-Shuqafa there is a mixture

between Roman and the Pharaonic arts, which is not only represented

in the architecture of the tomb, but also its engraving and

statues. This mixture may have perhaps resulted because the

opportunity in both Egypt and Alexandria gave rise to the

mixture of the Greek and Romans arts with the Pharaonic art

of Egypt which was prevalent in Egypt since Alexander's feet

trod its grounds. Or perhaps it was the desire of the tomb's

owner that the artist realize a mixture between both the Roman

and Egyptian arts as was the effect of religious scenes shown

in the drawings, and effect of Roman and Egyptian religions.

The catacomb is composed of a ground level construction

that probably served as a funerary chapel, a deep spiral stairway

and three underground levels for the funerary ritual and entombment.

The first level consists of a vestibule with a double exedra,

a rotunda and a triclinium. The second level, in its original

state, was the main tomb, with various surrounding corridors.

It was reached by a monumental staircase from the rotunda.

The third level is submerged in ground water, which has also

caused it to be saturated with sand. The Catacomb is one of

the most inspired monuments of Alexandrian funerary architecture,

following the conceptual design laid down in the Ptolemaic

period, but disposing the elements of the tomb on a vertical

rather than a horizontal axis.

The remains of an extensive mosaic pavement discovered

during the Sieglin Expedition near the entrance to Kom el-Shuqafa

and directly above the Hall of Caracalla allowed Schreiber

to reconstruct a large funerary chapel directly above the

spiral staircase that descends to the Catacomb. A possible

model for reconstructing this chapel, contemporaneous with

Kom el-Shuqafa, is preserved at the recently excavated site

of Marina el-Alamein, 96 kilometers west of Alexandria. That

structure is a large, broad building, entered on its long

side. It has a very symmetrically arranged core that is preceded

by a portico with eight Ionic columns.

The central part of this building beyond the portico

is entirely devoted to a large banquet room paved with rectangular

slabs of limestone and fitted with two stone banquet couches

with their legs and horizontal beams indicated in relief as

those of Ptolemaic Klinai. To the left and right of the banquet

room are two smaller rooms, presumably for service. At the

back fo the banquet hall is a monumental doorway flanked by

engaged semi-columns that opens onto a short corridor that

leads to a staircase down into the hypogeum.

At Kom el-Shuqafa, a shaft about six meters in diameter contains both the spiral staircase, which is preserved to a height of about ten meters, and the central light well around which the steps wind. Most other tombs at Alexandria have square shafts, but this one is round. These shafts were not only used to light the tombs, but to lower the bodies of the deceased down to the actual burial area. The wall that encloses the stairwell and separates it from the light well consists of squared blocks pierced by arched windows that have slanted sills in order to direct light downward onto the stairs. There are ninety-nine steps that decrease in height as they approach the surface, so that at the top there is almost no steps at all. This was designed for the tomb visitors so that after viewing the deceased in the lower levels, the climb back up to the surface would become easier as the visitor became tired from the climb out.

This spiral staircase only went as low as the first

floor and lead to a vestibule with two, opposed niches, known

as exedrae. These were actually seats where visitors could

rest. The niches were paved with alabaster and sheltered with

shell style conch-shaped semi-domes. The ceiling of these

niches were in the form of a semi dome ornamented as a shell.

This type of design can be dated to the Antoinini period of

Roman rule, or about the second century AD. There are also

some remains a mosaic floor.

The vestibule leads to the rotunda, which is the

focal point of the first level. It is a cylindrical shaft

surrounded by a ring-shaped ambulatory. The shaft is capped

by a dome supported by six pilasters. A low parapet between

the pilasters enclosed the shaft, setting it off from the

ambulatory. At the bottom of this shaft were found five stone

hands that were removed to the Greco-Roman Museum, but casts

were made of them that can be seen on the parapet.

To the left (southeast) of the rotunda the tombs

have a funeral banquet hall called a "Triclinium", which sits

to a right angle to the vestibule. The entrance of the triclinium

opens onto a huge room, nearly nine meters square, cut with

four freestanding piers with Doric anta capitals. Between

these piers are three rock-cut couches, each about two meters

wide, that form the typical U-shape so that the diners could

easily converse as they reclined. A raised ceiling cut above

the area segmented by the four piers provides the impression

of a light well and adds a sense of openness to the otherwise

featureless room. The two piers that face the entrance have

insets to hold lamps or torches, and on days of feasting the

benches would have surely been covered with elaborately patterned

mattresses and cushions, evidenced by their depiction on Ptolemaic

rock-cut klinai and on Roman sarcophagi outside Egypt. There

may have been tables made of wood or stone here, but they

have disappeared.

At a right angle to the triclinium and on an axis

with the vestibule, a wide staircase from the Rotanda, which

divides to accommodate the prompter's box (a covered shaft

to the third lower level), leads down to the second level

that contains the Main Tomb. This staircase is composed of

fifteen steps that lead to a narrow landing from which the

divided staircase of six additional steps continues to the

Main Tomb. This is a similar arrangement to Egyptian rock-cut

tombs, but is different than monumental staircases of the

Hellenistic period.