The Valley of the Kings

Geography of the Valley

The

first king of the New Kingdom, Ahmose of the 18th Dynasty,

built a pyramid-like structure at Abydos, which may or may

not have been his original tomb. But all the remaining rulers

of the period, except for the so-called Amarna interregnum,

had their tombs cut into the rocks of the West Bank at Thebes,

specifically at the Valley of the Kings. From Thutmose I in

the 18th Dynasty of the New Kingdom period, all the kings,

and occasionally high officials of that period, were buried

in the secluded wadi, or dry gully, which today is called

Valley of the Kings.

The

first king of the New Kingdom, Ahmose of the 18th Dynasty,

built a pyramid-like structure at Abydos, which may or may

not have been his original tomb. But all the remaining rulers

of the period, except for the so-called Amarna interregnum,

had their tombs cut into the rocks of the West Bank at Thebes,

specifically at the Valley of the Kings. From Thutmose I in

the 18th Dynasty of the New Kingdom period, all the kings,

and occasionally high officials of that period, were buried

in the secluded wadi, or dry gully, which today is called

Valley of the Kings.

The peak known in Arabic as el-Qurn was known in

ancient times as dehent, the Horn, and was sacred to the goddesses

Hathor and Meretseger, "She who loves Silence."

The

Valley, known as Biban el-Muluk, "doorway or gateway of the

kings," or, the Wadyein, meaning "the two valleys," is actually

composed of two separate branches. The main eastern branch,

called ta set aat, or "The Great Place," is where most of

the royal tombs are located, and in the larger, westerly branch

where only a few tombs were cut.

The

Valley, known as Biban el-Muluk, "doorway or gateway of the

kings," or, the Wadyein, meaning "the two valleys," is actually

composed of two separate branches. The main eastern branch,

called ta set aat, or "The Great Place," is where most of

the royal tombs are located, and in the larger, westerly branch

where only a few tombs were cut.

The Valley is hidden from sight, behind the cliffs,

which form the backdrop to the temple complex of Deir el-Bahri.

Though the most direct route to the valley is a rather steep

climb over these cliffs, a much longer, shallower, route existed

along the bottom of the valley. This was quite possibly used

by funeral processions, pulling funeral equipment by sledges

to the rock-cut tombs in the Valley.

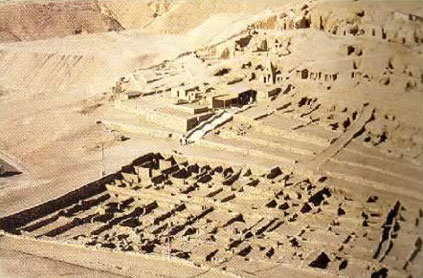

With

its worker’s village later called Deir el-Medina, the valley

was called the Place of Truth or Set Ma’at, in ancient times.

The workers of Deir el-Medina, who for generations since their

community was established, could reach the Valley in about

30 minutes by walking along the steep mountain paths. Today,

energetic folks may spend 45 minutes to an hour climbing the

paths leading from the north side of the amphitheater of Deir

el-Bahri and over the mountain ridge into the Valley of the

Kings. Their efforts would be rewarded by splendid views of

the Theban region.

With

its worker’s village later called Deir el-Medina, the valley

was called the Place of Truth or Set Ma’at, in ancient times.

The workers of Deir el-Medina, who for generations since their

community was established, could reach the Valley in about

30 minutes by walking along the steep mountain paths. Today,

energetic folks may spend 45 minutes to an hour climbing the

paths leading from the north side of the amphitheater of Deir

el-Bahri and over the mountain ridge into the Valley of the

Kings. Their efforts would be rewarded by splendid views of

the Theban region.

Tombs in the Valley

The Valley contains 62 tombs to-date, excavated by

the Egyptologists and archaeologists from many countries.

Not all of the tombs belonged to the king and royal family.

Some tombs belonged to privileged nobles and were usually

undecorated. Not all the tombs were discovered intact, and

some were never completed.

The powerful kings of the 18th and 19th Dynasties

kept the tombs under close supervision, but under the weaker

rulers of the 20th Dynasty, the tombs were looted, often by

the very workers or officials supposedly responsible for their

creation and protection. In order to prevent further thefts,

the mummies and some of their funerary objects were reburied

in two secret caches, not to be re-discovered until the 19th

century of the modern era.

Visitors to Egypt have often journeyed into the Valley

to view the accessible tombs, including Tut’s, but with the

increasing tourism, urban and industrial growth, pollution,

and rising groundwater, the tombs have suffered over the decades.

Today their access is rotated, so that a smaller number of

tombs are open at one time, and even then, many of the decorations

and walls can only be seen behind glass.

According to Diodorus and Strabo, and Greek and Latin

graffiti, two writers of ancient times, a few of the tombs

in the Valley of the Kings were known and visited by ancient

tourists during Ptolemaic times. Today, only a few of the

62

known tombs are accessible and open to the public. Eleven

of the tombs, including Tutankhamun’s, Ramesses VI, Amenhotep

II, and Seti I, have been set with electrical lighting.

62

known tombs are accessible and open to the public. Eleven

of the tombs, including Tutankhamun’s, Ramesses VI, Amenhotep

II, and Seti I, have been set with electrical lighting.

Right: Entrance to Tutankhamun's Tomb

The earliest king buried in the Valley was Thutmose

I, the latest, Ramesses XI. In 1922, Howard Carter found the

last and possibly most well-known of these tombs, that belonging

to the young King Tutankhamun. It lies directly opposite the

tomb of Ramesses IX. For all the amount of treasure that had

been found in this tomb, the space itself is small, and all

but one room was undecorated.

Directly across from Tutankhamun’s tomb lies KV5,

where work continues to uncover what may be the last resting

place of the 150 sons of Ramesses II.

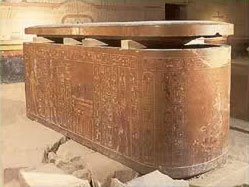

Ramesses

VI had one of the largest tombs in the valley. His tomb is

decorated with scenes from the books of the underworld, and

the burial chamber is dominated by the shattered remains of

the king’s massive granite sarcophagus.

Ramesses

VI had one of the largest tombs in the valley. His tomb is

decorated with scenes from the books of the underworld, and

the burial chamber is dominated by the shattered remains of

the king’s massive granite sarcophagus.

Left: Tomb of Ramesses VI

The tomb of Ramesses I, who had a brief reign, is

a single small chamber at the end of a steep corridor. It

bears some similarity in its decoration with the tomb of Horemheb,

while being more elaborate. The tomb of Merneptah, 13th son

and successor of Ramesses II, is badly damaged but worth visiting.

Psusennes I appropriated one of the sarcophagi for his own

burial at Tanis.

The

tomb of Thutmose III is the earliest-era tomb that can be

visited. Its walls are covered with 741 different deities

and its ceiling is spangled with stars. The first of the tombs

usually accessible is that of Ramesses IX, listed as tomb

6, right next to Tomb 55, now inaccessible.

The

tomb of Thutmose III is the earliest-era tomb that can be

visited. Its walls are covered with 741 different deities

and its ceiling is spangled with stars. The first of the tombs

usually accessible is that of Ramesses IX, listed as tomb

6, right next to Tomb 55, now inaccessible.

Right: Tuthmosis III Sarcophagus

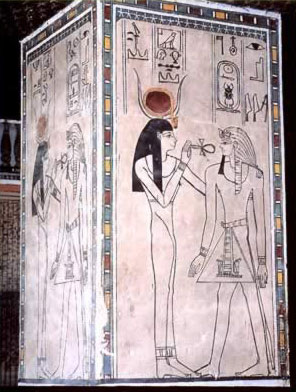

The tomb of Seti I is the largest and most elaborate

of the royal tombs. It is often closed to visitors because

of rock falls and a lack of ventilation. Giovanni Belzoni,

the Patagonian Samson, first entered this tomb in 1817 and

brought back the alabaster sarcophagus and canopic chest to

England, where they rest in the John Soane Museum. Some large

wooden statues of Seti I similar to the black and gilt statues

of Tutankhamun now stand in the British Museum.

The

tomb of Ramesses II was begun for his father, Seti I, but

abandoned, because the corridor cut into the adjacent tomb

of Amenmesse. Belzoni removed the cartouche-shaped sarcophagus

lid and it now rests in the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge.

The box sits in the Louvre.

The

tomb of Ramesses II was begun for his father, Seti I, but

abandoned, because the corridor cut into the adjacent tomb

of Amenmesse. Belzoni removed the cartouche-shaped sarcophagus

lid and it now rests in the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge.

The box sits in the Louvre.

Left: Column in tomb of Amenhotep II

Situated at the southern end of another wadi is the

tomb of Amenhotep II. In 1898, in its southwest chamber was

found one of the caches of royal mummies. This tomb’s seclusion

made it a good reburial place for the nine royal mummies placed

here in order to protect them from further depredations. Thutmose

IV, Amenhotep III, Siptah, and Seti II were among the re-buried.

Amenhotep II was found still lying in his own sarcophagus.

Along with royal tombs, tombs belonging to officials

were found more or less intact. One was Maiherpra, a Nubian

prince educated at court with the royal princes, one of which

became Amenhotep II. Subsequently Maiherpra held office under

that king.

History of Egyptology in the Valley

The Classical Greek writers Strabo and Diodorus Siculus

were able to report that the total number of Theban royal

tombs was 47, of which at the time only 17 were believed to

be undestroyed. Pausanias and others wrote of the pipe-like

corridors of the Valley, tombs into which travelers could

descend and admire the wall decorations.

Some of these travelers left their names and other

marks. The earliest datable graffito in the Valley was found

in the tomb of Ramesses VII, and can be dated to 278 BCE,

and the latest, left by a governor of Upper Egypt was dated

to 537 ACE. The French scholar Jules Baillet counted over

2000 Greek and Latin graffiti left over the Classical centuries,

along with a lesser number in Phoenician, Cypriot, Lycian,

Coptic, and other languages. Almost half of these were found

in the tomb of Ramesses VI, who was considered to be the fabled

Memnon himself.

After the Arabs came into Egypt in 641 ACE, interest

in the Valley waned considerably. It was not until the end

of the 16th century that once again travelers began once again

to take notice. Although the location of Thebes was clearly

marked on a map of 1595, in 1668 a Father Charles Francois

visited "the place of the mummies" and apparently did not

realize its significance. It was left to another Frenchman,

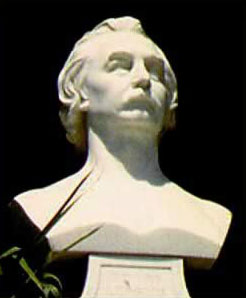

Father Claude Sicard, head of the  Jesuit

Mission in Cairo, traveling in Egypt between 1714 and 1726,

who visited in the Valley in 1708 and located 10 open tombs

including that of Ramesses IV. He wrote of the extensive wall

paintings and their colors.

Jesuit

Mission in Cairo, traveling in Egypt between 1714 and 1726,

who visited in the Valley in 1708 and located 10 open tombs

including that of Ramesses IV. He wrote of the extensive wall

paintings and their colors.

Left: Father Claude Sicard

Sicard’s notes for the most part were unfortunately

lost, and thus the first significant published account of

the Valley was left to an Englishman named Richard Pococke

in 1743. He apparently noted signs of about 18 tombs, though

believing that only nine of these could be entered. In 1768

a Scotsman named James Bruce visited Luxor and explored the

Valley. He visited the tombs of Ramesses IV and of Ramesses

III, henceforth known as "Bruce’s Tomb." The principal feature

of the latter tomb, for Bruce, were the fresco scenes of three

harps.

William George Brown visited the Valley in 1792,

and he left his name in the tomb of Ramesses III. He also

recounted one of the few extant accounts of contemporary Arab

interest and excavation at the site. Browne wrote that the

site had been explored "in the last 30 years" by a certain

son of a Sheikh Hamam, but it is unknown whether or not this

person was successful. Browne also described several tombs

to which he had access, three of which did not seem to tally

with descriptions given by Richard Pococke.

After

Napoleon’s Expedition in 1798, two Frenchmen named Prosper

Jollois and Edouard de Villiers du Terrage recorded the position

of 16 tombs. For the first time the existence of a western

branch of the valley was recorded, including the tomb of Amenhotep

III. Jollois and de Villiers were to publish their works in

the 19 volume Description de l’Egypte.

After

Napoleon’s Expedition in 1798, two Frenchmen named Prosper

Jollois and Edouard de Villiers du Terrage recorded the position

of 16 tombs. For the first time the existence of a western

branch of the valley was recorded, including the tomb of Amenhotep

III. Jollois and de Villiers were to publish their works in

the 19 volume Description de l’Egypte.

Right: Jean Francois Champollion

One of the great names of early Egyptology has to

be that of Champollion, for his work in translating the ancient

hieroglyphic symbols on the Rosetta Stone and thus opening

the door to a greater understanding of the lives of these

people. But though this work and his beautiful drawings published

in his Monuments de l’Egypte et de la Nubie left a brilliant

legacy for scholars who followed him, he also left a legacy

of shoddy and misguided destruction. Champollion and his companion

Rossellini removed two scenes from the tomb of Seti I, which

they brought to the Louvre and to a museum in Florence.

Giovanni Belzoni, called the Patagonian Samson, was

the first modern-era European to visit the Valley of the Kings.

He was sponsored by the Englishman Henry Salt, Consul-General

in Egypt in 1816. Among other treasures,  Belzoni

removed from Egypt the sarcophagus of Ramesses III from "Bruce’s

Tomb," and it now lies in the Louvre and the Fitzwilliam Museums.

To give him some credit, Belzoni also not only confirmed the

presence of the 47 tombs known to Classical writers, but added

a further 8 tombs to that list, including those of King Ay,

Prince Mentuherkhepshef, and Ramesses I. Belzoni’s most well-known

find in the Valley was the tomb of Seti I, the finest so far

found.

Belzoni

removed from Egypt the sarcophagus of Ramesses III from "Bruce’s

Tomb," and it now lies in the Louvre and the Fitzwilliam Museums.

To give him some credit, Belzoni also not only confirmed the

presence of the 47 tombs known to Classical writers, but added

a further 8 tombs to that list, including those of King Ay,

Prince Mentuherkhepshef, and Ramesses I. Belzoni’s most well-known

find in the Valley was the tomb of Seti I, the finest so far

found.

Left: Giovanni Belzoni

After Belzoni’s escapades, scholars began to emphasize

recording and studying what had been found in the Valley,

rather than simply searching for more tombs. John Gardner

Wilkinson, born in Chelsea, England in 1797 excavated in the

Valley in 1824 and in 1827-28.at his own expense. Except for

the West Valley, which he numbered separately, Wilkinson physically

assigned a number to each tomb entrance, still visible today.

Tombs KV1-21 are marked on the map of the main valley in his

Topographical Survey of Thebes of 1830.recorded in 1827 that

21 tombs were open to view, listing them in chronological

order. He copied scenes and inscriptions and then published

the first accurate account of the tombs, titled Topography

of Thebes, in 1830.

James

Burton was a contemporary of Wilkinson in Thebes. He began

a clearance of the tomb listed as KV20, which he had to abandon

due to "bad air" and only later would be proven by Howard

Carter to be the tomb of Thutmose I and Hatshepsut. Burton

also began a superficial examination of the tomb later called

KV5. This tomb would wait until the 20th century to prove

itself as the largest tomb to-date, most probably cut to serve

the family of Ramesses II. At least 50 of his children have

been found so far to have been buried therein. Burton published

no records of his work, though some 63 volumes of his notes

and drawings were given to the British Museum upon his death

in 1862.

James

Burton was a contemporary of Wilkinson in Thebes. He began

a clearance of the tomb listed as KV20, which he had to abandon

due to "bad air" and only later would be proven by Howard

Carter to be the tomb of Thutmose I and Hatshepsut. Burton

also began a superficial examination of the tomb later called

KV5. This tomb would wait until the 20th century to prove

itself as the largest tomb to-date, most probably cut to serve

the family of Ramesses II. At least 50 of his children have

been found so far to have been buried therein. Burton published

no records of his work, though some 63 volumes of his notes

and drawings were given to the British Museum upon his death

in 1862.

Karl Richard Lepsius followed both examples, that

of scholarly recording and that of removing artifacts from

their original place of rest. In 1844, Lepsius led a Prussian-backed

expedition to Egypt. After years of exploring, mapping, and

drawing pyramids, tombs, and monuments, including the Valley

of the King tombs, Lepsius returned  and

produced the twelve-volume work Denkmaler aus Agypten und

Athiopien. But he also sent out of Egypt 15,000 pieces, and

at one time, overthrowing a decorated column in Seti’s tomb

merely in order to remove a portion of it, leaving the rest

in wreckage on the floor.

and

produced the twelve-volume work Denkmaler aus Agypten und

Athiopien. But he also sent out of Egypt 15,000 pieces, and

at one time, overthrowing a decorated column in Seti’s tomb

merely in order to remove a portion of it, leaving the rest

in wreckage on the floor.

Left: Karl Richard Lepsius

In the latter half of the 19th century, this plundering

would come to a close. Auguste Mariette laid the foundations

of a national Egyptian museum and for a governmental antiquities

service. It was Mariette who discovered the Serapeum, the

burial place at Memphis of the sacred Apis bulls, and the

intact burial of Queen Ahhotep, mother of Ahmose, the founder

of the New Kingdom. But Mariette’s greatest contribution to

Egyptology was the formation of the Antiquities Service. As

Director-General, he was responsible for awarding concessions

to all excavators, monitoring all digs, and policing the export

of antiquities.

When the first cache of royal mummies was discovered

in 1881 at Hatshepsut’s temple of Deir el Bahri, world attention

was once and for all focused on the quiet valley, and the

first of many new excavations began in the area. Victor Loret

arrived in Luxor in 1898. Loret had been appointed as the

Director-General of the Antiquities Service, established by

Mariette in 1856. Only five days after he began to dig below

the cliffs under the Qurn, or "Horn" mountain, his team discovered

the tomb of Thutmose III. He added 16 tombs to the map of

the principal Valley. He also discovered the second cache

of royal mummies within the tomb of Amenhotep II.

But Loret was not well-liked, and upon his resignation

Maspero was reinstated. In 1899, Maspero appointed Howard

Carter to be Antiquities Inspector for Upper Egypt. His responsibilities

were to maintain all the sites of Upper Egypt and to grant

concessions for others to dig, rather than having the authority

to dig on his own. One of Carter’s claims to fame in this

job was that he installed the first electric lighting, handrails,

staircases and running boards in the royal tombs.

Financing

these improvements required the backing of investors, and

one such was the American Theodore Davis. Under his patronage,

Carter discovered the royal tomb of Thutmose IV, including

a wonderful royal chariot, and the tomb of Hatshepsut herself,

containing her sarcophagus and that of her father Thutmose

I.

Financing

these improvements required the backing of investors, and

one such was the American Theodore Davis. Under his patronage,

Carter discovered the royal tomb of Thutmose IV, including

a wonderful royal chariot, and the tomb of Hatshepsut herself,

containing her sarcophagus and that of her father Thutmose

I.

Right: Howard Carter

When Davis persuaded Maspero in 1903 that he could

no longer work with Carter, Maspero promoted Carter to Inspector

of Saqqara, but Carter resigned six weeks later and never

worked for the Antiquities Service again. Maspero replaced

him with James Quibell, but he too was eventually replaced,

by Arthur Weigall. Weigall was the one who broke through a

tomb entrance that Quibell had earlier discovered, to find

the rich burial goods and mummies of Yuya, Master of the King’s

Horse, and his wife Thuya, the parents of Tiye, wife of Amenhotep

III and mother of Amenhotep IV, later to rename himself Akhenaten.

More archaeologists and Egyptologists would follow,

and great finds would continue to be made. Many excavators

would return to Egypt and add astounding discoveries in the

Valley to their earlier finds. Howard Carter was one who kept

on working. For all the incredible efforts and discoveries

made in the Valley of the Kings, in past decades or within

just the past weeks, and all the contributions to the expansion

of our knowledge of the funerary practices and literature

and of the kingly history of ancient Egypt, all these seem

veritably overshadowed by the finds made that relate to just

one burial, the tomb and riches of the young King Tutankhamun.