Tutankhamun (King Tut)

At

this point, it almost seems to be repetitive to remind readers

that Tutankhamun (King Tut) was not a major player in Egypt

Pharaonic history, or at least, in comparison with other pharaohs.

In fact, prior to Howard Carter's discovery of his tomb, almost

nothing was known of him and interestingly, the one disappointment

in Carter's discover was that there was little in the way

of documentation found within his tomb. Therefore, we still

know relatively little about Tutankhamun. For example, even

who is father was remains a topic of some debate. That has

not prevented writers from producing volumes of material on

the Pharaoh.

At

this point, it almost seems to be repetitive to remind readers

that Tutankhamun (King Tut) was not a major player in Egypt

Pharaonic history, or at least, in comparison with other pharaohs.

In fact, prior to Howard Carter's discovery of his tomb, almost

nothing was known of him and interestingly, the one disappointment

in Carter's discover was that there was little in the way

of documentation found within his tomb. Therefore, we still

know relatively little about Tutankhamun. For example, even

who is father was remains a topic of some debate. That has

not prevented writers from producing volumes of material on

the Pharaoh.

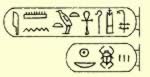

We believe Tutankhamun ruled Egypt between 1334 and

1325 BC. He was probably the 12th ruler of Egypt's 18th Dynasty.

Tutankamun was not given this name at birth, but

rather Tutankhaten (meaning "Living Image of the Aten), squarely

placing him in the line of pharaohs following Akhenaten, the

heretic pharaoh, who was most likely his father. His mother

was probably Kiya, though this too is in question. He changed

his name in year two of his rule to Tutankhamun (or heqa-iunu-shema,

which means "Living Image of Amun, Ruler of Upper Egyptian

Heliopolis", which is actually a reference to Karnak) as re

reverted to the old religion prior to Akhenaten's upheaval.

Even so, this did not prevent his name from being omitted

from the classic kings lists of Abydos and Karnak. We may

also find his named spelled Tutankhamen or Tutankhamon, among

other variations. His throne name was Neb-Kheperu-re, which

means "Lord of Manifestations is Re.

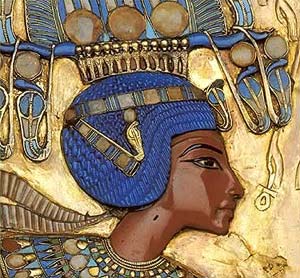

Left:

Tutankhamun from the back of his gold throne.

Left:

Tutankhamun from the back of his gold throne.

We do know that he spent his early years in Amarna,

and probably in the North Palace. He evidently even started

a tomb at Amarna. At age nine he was married to Ankhesenpaaten,

his half sister, and later Ankhesenamun. We believe Ankhesenpaaten

was older then Tutankhamun because she was probably of child

bearing age, seemingly already having had a child by her father,

Akhenaten. It is possible also that Ankhesenamun had been

married to Tutankhamun's predecessor. It seems he did not

succeed Akhenaten directly as ruler of Egypt, but either an

older brother or his uncle, Smenkhkare (keeping in mind that

there is much controversy surrounding this king). We believe

Tutankhamun probably had two daughters later, but no sons.

At the end of Akhenaten's reign, Ay and Horemheb,

both senior members of that kings court, probably came to

the realization that the heresy of their king could not continue.

Upon the death of Akhenaten and Smenkhkare, they had the young

king who was nine years old crowned in the old secular capital

of Memphis. And since the young pharaoh had no living female

relatives old enough, he was probably under the care of Ay

or Horemheb or both, who would have actually been the factual

ruler of Egypt.

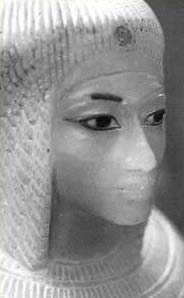

Right:

Kiya, a lesser wife of Akhenaten who was probably Tutankhamun's

mother.

Right:

Kiya, a lesser wife of Akhenaten who was probably Tutankhamun's

mother.

We know of a number of other officials during the

reign of Tutankhamun, two of which include Nakhtmin, who was

a military officer under Horemheb and a relative of Ay (perhaps

his son) and Maya, who was Tutankhamun's Treasurer and Overseer

of the Place of Eternity (the royal necropolis). Others included

Usermontju and Pentu, his to viziers of upper and lower Egypt,

as well as Huy, the Viceroy of Nubia.

Immediately after becoming king, and probably under

the direction of Ay and Horemheb, a move was made to return

to Egypt's traditional ancient religion. By year two of his

reign, he changed his, as well as Ankhesenpaaten's name, removing

the "aten" replacing it with "amun". Again, he may have had

nothing to do with this decision, though after two years perhaps

Ay's and Horemheb's influence had effected the boy-king's

impressionable young mind.

One reason why Tutankhamun was not listed on the

classical king lists is probably because Horemheb, the last

ruler of the 18th Dynasty, usurped most of the boy-king's

work, including a restoration stele that records the reinstallation

of the old religion of Amun and the reopening and rebuilding

of the temples. The ownership inscriptions of other reliefs

and statues were likewise changed to that of Horemheb, though

the image of the young king himself remains obvious. Even

Tutankhamun's extensive building carried out at the temples

of Karnak and Luxor were claimed by Horemheb. Of course, we

must also remember that little of the statues, reliefs and

building projects were actually ordered by Tutankhamun himself,

but rather his caretakers, Ay and Horemheb.

Left:

Kiya, a lesser wife of Akhenaten who was probably Tutankhamun's

mother.

Left:

Kiya, a lesser wife of Akhenaten who was probably Tutankhamun's

mother.

His building work at Karnak and Luxor included the

continuation of the entrance colonnades of the Amenhotep III

temple at Luxor, including associated statues, and his embellishment

of the Karnak temple with images of Amun, Amunet and Khonsu.

There were also a whole range of statues and sphinxes depicting

Tutankhamun himself, as well as a small temple in the king's

name. We also know, mostly from fragments, that he built at

Memphis. At Kawa, in the far south, he built a temple. A pair

of granite lions from that temple today flank the entrance

to the Egyptian Sculpture Gallery at the British Museum.

Militarily, little happened during the reign of Tutankhamun,

a surprising fact considering that Horemheb was a well known

general. Apparently there were campaigns in Nubia and Palestine/Syria,

but this is only known from a brightly painted gesso box found

in Tutankhamun's tomb. It portrays scenes of the king hunting

lions in the desert and gazelles, while in the fourth scene

he is smiting Nubians and then Syrians. There are paintings

in the tomb of Horemheb and as well as the tomb of Huy that

seem to confirm these campaigns, though it is unlikely that

the young Tutankhamun actually took part in the military actions

directly. The campaigns in Palestine/Syria met with little

success, but those in Nubia appear to have gone much better.

Though we know that Tutankhamun died young, we are

not certain about how he died until very recently. Both forensic

analysis of his mummy and clay seals dated with his regnal

year support his demise at the age of 17 or no later then

18. As to how he died, a small sliver of bone within the upper

cranial cavity of his mummy was discovered from X-ray analysis,

suggesting that his death was not due to illness. It has been

suggested that he was possibly murdered, but it is also just

as likely the result of an accident. In fact, a recent medical

examination now seems to indicate that he may very well have

died from infection brought about by a broken leg.

Yet it is clear that others certainly had eyes on

the throne.

Right:

Tut's famous gold funeral mask.

Right:

Tut's famous gold funeral mask.

After Tutankhamun's death, Ankhesenamun was a young

woman surrounded by powerful men, and it is altogether obvious

that she had little interest or love for any of them. She

wrote to the King of the Hittites, Suppiluliumas I, explaining

her problems and asking for one of his sons as a husband.

Suspicious of this good fortune, Suppiluliumas I first sent

a messanger to make inquiries on the truth of the young queen's

story. After reporting her plight back to Suppilulumas I,

he sent his son, Zannanza, accepting her offer. However, he

got no further than the border before he was murdered, probably

at the orders of Horemheb or Ay, who, both had both the opportunity

and the motive. So instead, Ankhesenamun married Ay, probably

under force, and shortly afterwards, disappeared from recorded

history. It should be remembered that both Ay and Horemheb

were military men, but Ay was much older then Horemheb, and

was probably the brother of Tiy who was the wife of Amenhotep

III. Amenhotep III was most likely Tutankhamun's grandfather.

He was also probably the father of Nefertiti, the wife of

Akhenaten. Therefore, he got to go first, as king, followed

a short time later by Horemheb.

Tutankhamun's famous tomb is located in the Valley

of the Kings on the West bank across from modern Luxor (ancient

Thebes). It is certainly less magnificent then other pharaohs

of Egypt, yet, because of it, Tutankhamun has remained in

our memory for many years, and will probably continue to do

so for many years to come. Regardless of all the myths surrounding

his tomb's discovery, including the "curse of the mummy" and

other media hype, it is all a blessing to the boy-king. The

ancient pharaohs believed that if their name was remembered,

their soul would live on, so not even the powerful Rameses

the Great's soul can be as healthy as King Tut's.

See also: