Excavating the Tomb of Tutankhamun

The

tomb of Tutankhamun, which is today designated as KV 62, was

number 4.33 in Howard Carter's sequence of discoveries since

1915. It did not take Lord Carnarvon and Carter long to appreciate

the enormity of the discovery and its implications. While

Arthur Callender, a close friend of Carter, had been helping

him, more assistance in clearing the tomb would certainly

be needed. When, soon after the discovery, Albert Lythgoe,

then Curator of the Metropolitan Museum's Egyptian Department,

cabled his congratulations and offered help, Carter took him

at his word, responding:

The

tomb of Tutankhamun, which is today designated as KV 62, was

number 4.33 in Howard Carter's sequence of discoveries since

1915. It did not take Lord Carnarvon and Carter long to appreciate

the enormity of the discovery and its implications. While

Arthur Callender, a close friend of Carter, had been helping

him, more assistance in clearing the tomb would certainly

be needed. When, soon after the discovery, Albert Lythgoe,

then Curator of the Metropolitan Museum's Egyptian Department,

cabled his congratulations and offered help, Carter took him

at his word, responding:

"Thanks message [of congratulations]. Discovery

colossal and need every assistance. Could you consider load

of Burton in recording in time being? Costs to us. Immediately

reply would oblige. Every regard, Carter, Continental, Cairo."

Close ties had already existed between Carter, Carnarvon

and the Metropolitan Museum, and so Carter was granted his

request. In due course, the Metropolitan Museum's generosity

would be rewarded when Carter helped them acquire the Carnarvon

collection.

However, within a matter of days, Carter received

other offers of help. On December 9th Alfred Lucas, a chemist

with the Egyptian Government, came forward. With him aboard,

the clearance of Tutankhamun's tomb seems to have been the

first ever archaeological expedition to have its own resident

chemist.

Then on December 12th Arthur Mace, an Egyptologist

with the Metropolitan Expedition, was also put at Carter's

disposal. Six days later, James Breasted, Director of the

Oriental Institute in Chicago arrived to begin work on the

seal impressions which covered the plastered blockings. The

Metropolitan team also provided him with Hauser and Hall,

two architects who began work on drawing a plan of the objects

in situ. Then, on January 3rd, Alan Gardiner, a British philologist,

arrived to start work on the inscriptions.

Others would eventually join the team, including

Percy Newberry, another of Carter's old friends. It became

a showpiece of academic cooperation that would in time also

draw in Douglas Derry of the Cairo Anatomy School, and Seleh

Bey Hamdi of Alexandria to conduct the postmortem examination

of the mummy, Battiscombe Gunn to  work

on the ostraca for the final publication, L. A. Boodle, a

botanist from Kew Gardens, James R. Ogden, a Harrogate jeweler

to report on aspects of the gold work, Alexander Scott and

H. J. Plenderleith of the British Museum for analytical assistance,

G. F. Hulme of the Geological Survey of Egypt, and others.

work

on the ostraca for the final publication, L. A. Boodle, a

botanist from Kew Gardens, James R. Ogden, a Harrogate jeweler

to report on aspects of the gold work, Alexander Scott and

H. J. Plenderleith of the British Museum for analytical assistance,

G. F. Hulme of the Geological Survey of Egypt, and others.

Part of the reason that there was so much politics

surrounding the discovery and excavation of the tomb of Tutankhamun

was that Howard Carter was a very advanced excavator for his

time. It is said that anyone else would have had the tomb

cleared and the objects it contained on display within a month

of the tomb's discovery, but it took Carter almost a decade

to carefully preserve and remove the treasures to Cairo. The

difference shows the caution with which Carter approached

this undertaking, which more resembles the efforts of modern

excavators.

Of course, most of the political challenges came

in the first two seasons of work, creating distractions and

difficulties, but afterwards, Carter and his team settled

into a thorough and methodical routine, maintaining  complete

records for each discovery and working to preserve each antiquity

as they were brought out of the tomb. The excavation used

the tomb of Ramesses XI (KV4) as a storeroom for supplies

and for minor finds from the stairwell and corridor, and later

the tomb of Seti II (KV15) was turned into a secure field

conservation laboratory and photographic studio. Also, KV55,

just across the path from the Tut's tomb, was made into a

darkroom for Harry Burton.

complete

records for each discovery and working to preserve each antiquity

as they were brought out of the tomb. The excavation used

the tomb of Ramesses XI (KV4) as a storeroom for supplies

and for minor finds from the stairwell and corridor, and later

the tomb of Seti II (KV15) was turned into a secure field

conservation laboratory and photographic studio. Also, KV55,

just across the path from the Tut's tomb, was made into a

darkroom for Harry Burton.

Howard Carter established a routine for processing

what must have seemed like an endless flow of treasures from

the tomb. Each object or group of objects was given a reference

number. The main reference numbers ranged from 1 to 620, though

there were subdivisions for objects within a numbered group

denoted by the use of single or multiple letters (a, b, c,

etc). Additional subdivisions were noted by bracketed Arabic

numerals. Group no. 620 is anomalous in that it was given

subdivisions numbered from 1 to 123. (i.e. 620:1 to 620:123).

The distribution of object numbers throughout the

tomb was as follows:

1a-3

4

5a-12t

13

14-170

28

172-260

261-336

171

337-620:123

|

Entrance staircase

first sealed doorway

Corridor

second sealed doorway

Antechamber

sealed doorway into the Burial Chamber

Burial Chamber

Treasury

partially dismantled Annex blocking

Annex

|

After

objects in the tomb were provided with reference numbers,

photographs were taken of the items in situ with and without

the reference number cards. The camera was repositioned several

times in order to show every object at least once in one of

the shots. A brief description was also provided, as well

as a sketch if appropriate, on a numbered record card (by

Carter or Mace), and the place of the objects discovery was

located on a ground plan of the tomb (prepared by Hall and

Hauser). Afterwards, the piece was removed to the laboratory

for treatment by Lucas and Mace, where more photographs were

made. After the conservation of the object was completed,

a further photograph was made. This routine was carried out

for many thousands of objects, over several seasons, sometimes

in sweltering heat, and under pressure from the press, who

were soon complaining about the excessive time the clearance

was taking. There was also a constant flow of visitors to

the tomb, including some 12,000 at the height of the King

Tut hysteria between January 1 and March 15th, 1926.

After

objects in the tomb were provided with reference numbers,

photographs were taken of the items in situ with and without

the reference number cards. The camera was repositioned several

times in order to show every object at least once in one of

the shots. A brief description was also provided, as well

as a sketch if appropriate, on a numbered record card (by

Carter or Mace), and the place of the objects discovery was

located on a ground plan of the tomb (prepared by Hall and

Hauser). Afterwards, the piece was removed to the laboratory

for treatment by Lucas and Mace, where more photographs were

made. After the conservation of the object was completed,

a further photograph was made. This routine was carried out

for many thousands of objects, over several seasons, sometimes

in sweltering heat, and under pressure from the press, who

were soon complaining about the excessive time the clearance

was taking. There was also a constant flow of visitors to

the tomb, including some 12,000 at the height of the King

Tut hysteria between January 1 and March 15th, 1926.

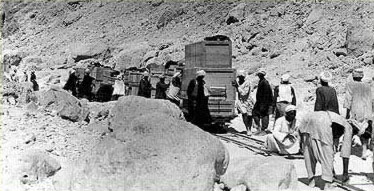

Clearance

of the Antechamber was begun on December 27th 1922. It took

seven weeks to finish, and used up more than a mile of cotton

wadding and 32 bales of calico to secure the objects. Afterwards,

and at the end of each successive season, the objects were

crated up with extreme care using hundreds of feet of timber,

and transported to the Nile river using the human powered

Decauville (narrow gauge) railway. Though only a relatively

short distance, the train track was not permanent and Carter

was given only a meager number of rail-lengths that had to

be constantly "leapfrogged", so it took some 15 hours to move

the train to the river during the heat of the summer months.

Clearance

of the Antechamber was begun on December 27th 1922. It took

seven weeks to finish, and used up more than a mile of cotton

wadding and 32 bales of calico to secure the objects. Afterwards,

and at the end of each successive season, the objects were

crated up with extreme care using hundreds of feet of timber,

and transported to the Nile river using the human powered

Decauville (narrow gauge) railway. Though only a relatively

short distance, the train track was not permanent and Carter

was given only a meager number of rail-lengths that had to

be constantly "leapfrogged", so it took some 15 hours to move

the train to the river during the heat of the summer months.

Only the gold coffin and mask were not transported

by river. They were conveyed by a train in a special "Service

Car" with an armed guard from the Egyptian army.

At the end of each season, for security against not

only theft but also floods, the tomb entrance was covered

over with a watertight wooden blocking erected over a wooden

portcullis, and guarded by a local policeman.

Carter would later tell us that:

"It had been our privilege to find the most important

collection of Egyptian antiquities that had ever seen the

light, and it was for us to show that we were worthy of the

trust."

See also: